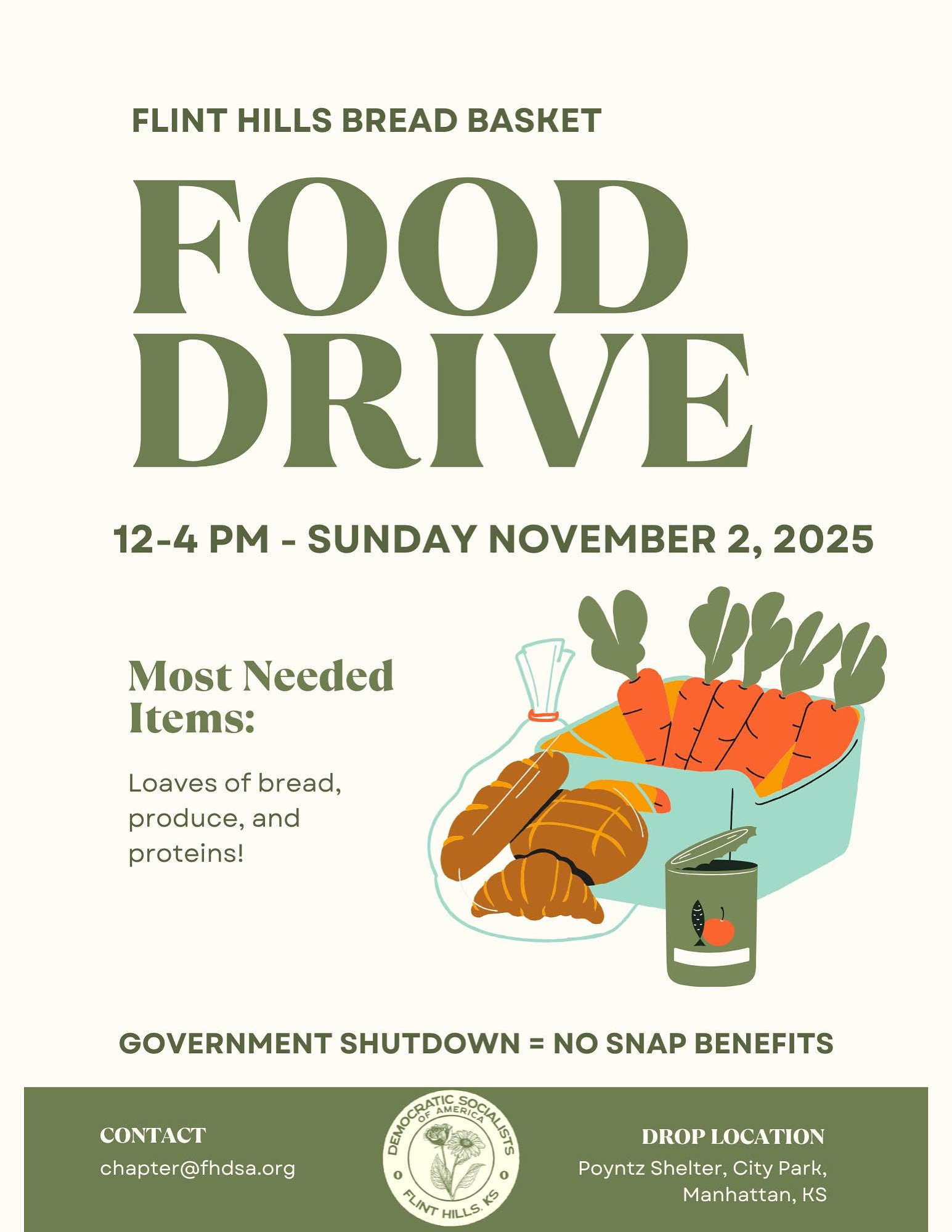

Recently, the chapter of Democratic Socialists of America for which I serve on the steering committee organized a food drive for a local food pantry, the Flint Hills Breadbasket. The number of individuals and families coming to the pantry had surged during the federal government shutdown, and the staff told us they were short on staples. We pulled the drive together during the last week of October, just before SNAP benefits were scheduled to lapse. We reached out to local organizations, contacted churches, and shared our flyer across various Manhattan-area Facebook groups.

What struck me almost immediately was how familiar this all felt. This is what people do when they see a need: they organize, they redistribute, they pool resources so no one falls through the cracks. Many of the same people who rolled their eyes at “welfare” rhetoric or repeated the usual talking points about “lazy people and ‘illegals’ on SNAP” showed up with boxes of canned goods, diapers, and grocery-store gift cards. The myth that poor people are simply unwilling to work seems to evaporate when you refuse to let your neighbors go without. In the simplest terms, the food drive was socialism in practice. Collective responsibility. Mutual care. Meeting needs.

But alongside the generosity, something else surfaced. A number of supportive community members helped us advertise by creating and sharing their own alternative versions of our flyer—versions that kept our contact information but quietly removed the DSA logo. What this told us was that they wanted to help but needed to distance themselves from “the S-word.” They feared the implications of being seen as aligned with socialism, even while actively participating in the very work socialists argue for. That contradiction is not personal. It is ideological. It’s the product of a sustained propaganda machine that has, for generations, conditioned Americans to fear a word whose content they enact daily.

Recently, the chapter of Democratic Socialists of America for which I serve on the steering committee organized a food drive for a local food pantry, the Flint Hills Breadbasket. The number of individuals and families coming to the pantry had surged during the federal government shutdown, and the staff told us they were short on staples. We pulled the drive together during the last week of October, just before SNAP benefits were scheduled to lapse. We reached out to local organizations, contacted churches, and shared our flyer across various Manhattan-area Facebook groups.

What struck me almost immediately was how familiar this all felt. This is what people do when they see a need: they organize, they redistribute, they pool resources so no one falls through the cracks. Many of the same people who rolled their eyes at “welfare” rhetoric or repeated the usual talking points about “lazy people and ‘illegals’ on SNAP” showed up with boxes of canned goods, diapers, and grocery-store gift cards. The myth that poor people are simply unwilling to work seems to evaporate when you refuse to let your neighbors go without. In the simplest terms, the food drive was socialism in practice. Collective responsibility. Mutual care. Meeting needs.

But alongside the generosity, something else surfaced. A number of supportive community members helped us advertise by creating and sharing their own alternative versions of our flyer—versions that kept our contact information but quietly removed the DSA logo. What this told us was that they wanted to help but needed to distance themselves from “the S-word.” They feared the implications of being seen as aligned with socialism, even while actively participating in the very work socialists argue for. That contradiction is not personal. It is ideological. It’s the product of a sustained propaganda machine that has, for generations, conditioned Americans to fear a word whose content they enact daily.

The conditioning runs deep. For most of the last century, Americans have been taught to equate any form of collective provision with tyranny. Propaganda didn’t just attack socialist governments abroad; it severed the concept of socialism from the practices that define it. Mutual aid became “charity.” Public goods became “handouts.” Structural inequality became “personal responsibility.” And whenever a socialist movement or government abroad posed even a modest threat to Western dominance, the United States and its allies intervened, through sanctions, sabotage, coups, economic strangulation, or outright military force. Then, after those interventions destabilized or collapsed the targeted society, the result was held up as “proof” that socialism can’t work. Capitalism protects itself through story as much as through power.

NATO’s original design fits the same pattern. The alliance openly positioned itself as a barrier to communist influence, not because communist societies were uniquely repressive, but because they removed labor and natural resources from Western corporate extraction. Alternatives are dangerous to a system that depends on there being no alternatives. So the messaging had to be relentless: socialism is dangerous, socialism is foreign, socialism is failure. The end result is a culture where people would rather erase a small logo from a flyer than risk being seen supporting an idea they quietly practice every day.

And yet, despite all of this, the reality keeps breaking through. When we set up in the city park, we expected a modest turnout. What happened instead pushed past anything we imagined. In four hours, the community delivered over $1,000 in cash donations and more than 3,600 pounds of food and household essentials. We actually collected more than our own group could physically handle, and it was strangers, people we had never met, who stepped in, lifted boxes, loaded cars, and helped shuttle everything to the Flint Hills Breadbasket. No one asked whether the families receiving those donations “deserved” them. No one performed ideological litmus tests. People simply acted.

This is the part of the story Americans are taught not to see. Even after a century of anti-socialist propaganda, the impulse toward collective care has not disappeared. The fear is in the language, not the practice. The “S-word” has been buried under decades of deliberate distortion, but the behaviors that make socialism viable keep resurfacing in moments exactly like this. The work ahead is not to invent a new political tradition. It is to name what people are already doing, and to reclaim the vocabulary that propaganda tried to take from us.